Shopping center landlords in North America and the U.K. are adapting to demographic shifts by tailoring their properties to appeal to consumers from China, India, South Korea and elsewhere in Asia. Their efforts include new or repositioned malls, grocery-anchored shopping centers and even “retail condos” — in which most tenants own their own real estate, a practice imported from Asia itself.

As Pacific and South Asian populations grow in these mature markets, more companies will try to capitalize on rising demand for Asian-centric retail, observers say. The challenge is to figure out when and how to forge ahead with strategies that can involve embracing new real estate formats, communicating through translators or pitching space to mom-and-pops with unfamiliar goods from far-off lands. Sometimes it all starts with a flash of inspiration. “When my business partners and I came across a derelict bus depot, right in the middle of Green Street [in East London], it occurred to us that we could do something very special with the space,” said Bob Popat, a principal at ACR Investments, a London-based development firm. Now, two years later this past March, some 12,000 shoppers flocked to the grand opening of ACR’s East Shopping Centre — billed as Europe’s first mall for shoppers from South Asian countries such as Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

Green Street is already a vibrant shopping district for South Asians, with colorful sari shops and arabesque groceries and restaurants, Popat says. But in the U.K., opening a 70,000-square-foot boutique mall specifically for South Asians is quite a departure, he says. “The U.K. still has a strong High Street culture,” said Popat. “I mean, London’s Oxford Street is Europe’s busiest shopping street. Covered or indoor shopping centers are atypical in the U.K. for the South Asian community.”

East Shopping Centre encompasses 35 double-story units plus an Arab-style, 17-tenant marketplace called The Souk. Most of the tenants — they include South Asian fashion designers, a beauty salon, costume jewelry boutiques, mobile phone vendors and shoe stores — are family-owned and bear names like Bidaai or Raishma Couture Lals. At the grand opening, shoppers lined up in the food court for the likes of Brioche Burgers, Pita Pit, Shinde’s and Urban Chocolatier. “We were really happy with the turnout,” said Popat. “I spoke with someone who drove down all the way from Leicester — around a two-hour drive — just to shop for his son’s wedding.”

Other Asian-focused projects are emerging, thanks to big changes in the trade areas of existing malls. In the early 1990s, when the McCarthy Ranch retail complex opened in Milpitas, Calif., Asians made up about 35 percent of the surrounding population. Today they number about 70 percent. With its focus on conventional retail, McCarthy Ranch fell on hard times as the area’s demographic profile changed, but now Canadian developer Torgan Group is moving forward with a strategic response: turning the property into what it bills as the first Asian-centric enclosed mall in the U.S., according to James M. Kessler, founder and president of Stonehenge Property Group, development adviser on the project. Pacific Mall Silicon Valley, as the project is called, is slated to open in 2017 and will offer about 300 small shops and a 240-room hotel. The 276,000-square-foot mall will reportedly cost $100 million to build and will include a cultural center for stage shows and public events.

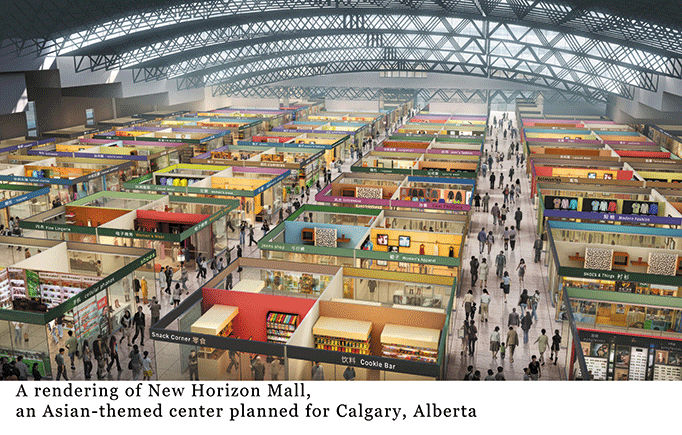

The mall is modeled after Torgan Group’s 450-store Pacific Mall, which is in Toronto, where ethnic minorities are likely to exceed 50 percent of the population by 2017, according to Statistics Canada. “Pacific Mall is highly successful and one of the top tourist destinations in Canada,” Kessler said. “Because of this, it is one of only three shopping centers in the country that are allowed to operate 365 days a year, even on national holidays.” Little wonder Torgan Group, along with partner MPI Property Group, is pressing ahead with yet another Asian-themed mall, this one in Calgary: New Horizon Mall. This 320,000-square-foot mall will reportedly boast some 500 retail tenants and is slated to open in 2017.

Unlike conventional malls in North America, all three Torgan Group projects are based on a retail-condo model in which tenants actually buy their spaces rather than lease them, Kessler says. The model, which appeals to first- and second-generation immigrants in particular, is commonplace across Asia, he says. “Culturally, ownership of the property can be very important,” he said. “Once Asian immigrants are third-generation or later, then they are much more in tune with what I would call Western-style [leased] shopping center models.”

In fact, Western-style shopping centers that focus on Asian consumers are growing in popularity as well, according to James Chung, executive managing director of DTZ Retail/Terranomics. In the Bay Area, these properties tend to be anchored by expanding Asian-focused chains, such as Marina Food, Pacific Market or Seafood City, he says. Asian-American supermarket 99 Ranch heads the lineup at Cupertino (Calif.) Village, which is undergoing a $16 million renovation to broaden its appeal to Asian shoppers, Chung notes. All told, 99 Ranch operates about 35 stores across California, Nevada, Texas and Washington. When developers want to refocus the demographic appeal of the centers, a critical first step is to lure an anchor like 99 Ranch, Chung says. “If you are able to procure a strong ethnic-Asian anchor tenant, typically the small shops and restaurants will follow,” he said. “It also helps if the anchor is in the daily-needs space; when you have those daily trips, the cycle of customers coming in and out of the center creates a lot of energy.”

When it comes to finding the best small-shop tenants for Asian-focused centers, some old-fashioned pavement-pounding is often the best approach, according to Greg Maloney, president and chief executive of JLL’s retail group. In the past JLL has dispatched brokers to parts of Pleasant Hill Road, in Atlanta, to scout for stores and restaurants that have scored a hit with local Chinese, Japanese and Korean shoppers, Maloney says. “You go in and talk to them and say, ‘You’re so busy here that you’re running out of space, but we’ve got a great space for you over at our mall,’” he said. “Whether it’s food or clothing, that’s how you grab them.”

But what if the prospect in question speaks primarily Lao or Vietnamese? To cross these linguistic and cultural barriers, hiring translators or multilingual brokers may be essential, experts say. In Chung’s leasing efforts for Cupertino Village, he has at times enlisted the help of a Mandarin-speaking translator. Kessler routinely works with Milpitas-based GD Commercial Real Estate, which employs brokers who speak Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Thai and Vietnamese. “Even sophisticated multiunit operators do not always speak English as their primary language,” Chung said. Experts in the media-consumption habits of local ethnic groups can also help developers maximize their marketing dollars, says Kessler. “You need to know what publications and platforms will be most effective at reaching people from different cultures,” Kessler said. “Some are tech-savvy, but for others it has got to be print.”

Some projects may focus narrowly on shoppers from a single Asian national group, but The Globe, a mall that is on the drawing board for Fremont, Calif., will seek to serve a range of Asian cultures. The 450,000-square-foot shopping center, announced just this spring by American Pacific International Capital, is a conversion of an existing retail-hotel development. It will feature themed villages focusing on various cultures, says Kelly Kline, economic development director for the city of Fremont. “It is being set up so that you can experience different parts of Asian cuisine and culture all in one place,” she said. “Each of these different villages will be built out in phases.” The themed areas of the $200 million project reportedly will be called Indus (India), JK Town (Japan-Korea), Siam Village (Thailand) and Sino Village (China), with a possible Europe-themed village as well.

About 50 percent of the population in Fremont — with its 1 million people in total, it is the fourth-largest city in the Bay Area — traces its ancestry to one Pacific or South Asian country or other, Kline notes. In addition to an outdoor events space, the Globe will focus heavily on restaurants rather than conventional anchor stores, says Christina Briggs, Fremont’s economic development manager. “It’s all about the food experience,” Briggs said. “The industry is starting to recognize that food can serve as an anchor. Often, getting something to eat is what drives people out of their homes.”

This highlights one of the potential advantages of Asian- or other ethnic-focused shopping centers: Authentic cuisine served up by talented first- and second-generation chefs can thrill foodies of just about any ethnic background. “It’s the whole theme of dining as entertainment,” Kline said. “Whether you’re talking about teppanyaki concepts or shabu-shabu or barbecue or hot pot, they all tend to be group-oriented. The atmosphere is different, because you’re participating in your meal. You don’t see restaurants like these everywhere. It’s not like, ‘Oh, another one of those.’”

So when should landlords start thinking about changing the demographic focus of their malls? In some markets the unfortunate reality is that this may be a survival strategy for lagging properties with few other choices, Maloney says. “Simply put, some of these properties have to go all the way down to their lowest point and then build back up,” he said. “A mall that was driving $40 per square foot in rents in its heyday might, after conversion, bring in $15 a foot. From a financial standpoint, that isn’t good.” But it all depends on the market in question. The robust Asian population in the Bay Area continues to drive solid rents, Chung says. “In Cupertino, occupancy costs have been going through the roof all around the market,” he said. “In many cases, these are not B- or C-class centers, where tenants are getting a discount rate. If anything, it’s the opposite.”

The success of the Bay Area centers could foreshadow the long-term potential of ethnic-oriented shopping centers elsewhere. Kessler, for one, says he frequently urges his colleagues in the shopping center industry to learn more about ethnic-focused retail. By about 2020, after all, upwards of half the children in the U.S. will belong to a minority race or ethnic group, according to the Census Bureau, and the “two or more races” category will be the fastest-growing over the next 46 years. “This is where things are going,” Kessler said. “We need to understand that doing the standard, everyday chain stores isn’t always the right answer. By getting in front of these trends, we can make the most of them.”