What has made grocery stores the stable workhorse of the Marketplaces Industry for decades? Don’t miss C+CT’s story from earlier this week: Grocery Stores’ Enduring Appeal to Shoppers, Investors and Developers.

1916: Self-Service

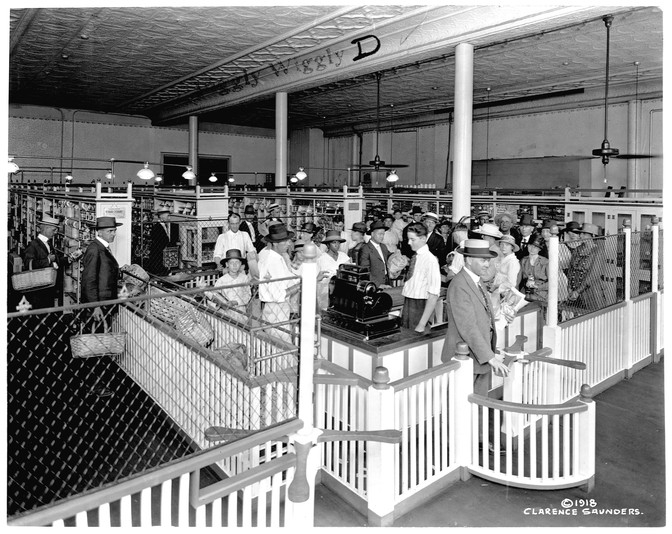

Entrepreneur Clarence Saunders opened the first Piggly Wiggly in Memphis. Shoppers previously handed clerks lists of the desired items, and Saunders replaced that process with self-service baskets. Piggly Wiggly now has 503 locations.

Clarence Saunders took this photo of one of his stores in 1918.

1930: The Supermarket

The King Cullen in Long Island’s Franklin Square, New York, closed in July 2022 after 48 years.

Former Kroger employee Michael Cullen launched what the Smithsonian Institution considers the first “true supermarket,” opening the first King Kullen in a 6,000-square-foot former garage in Queens, New York. His slogan: “Pile it high. Sell it low,” though some sources replace “low” with “cheap.” Similar to Piggly Wiggly, Cullen prioritized self-service but combined it with new ideas: separated food departments, volume discount selling, loss leaders and spacious customer parking. King Kullen still operates 27 stores on Long Island in New York.

1936: The Shopping Cart

Grocer Sylvan Goldman noticed that customers would stop shopping once their handheld wicker baskets filled. He wondered if folding chairs could be fitted with wheels and with baskets attached on and below the seat. A year later, he introduced his wire-enforced “folding basket carrier.” Shoppers wouldn’t use them at first, so he hired faux shoppers to walk around filling them and instructed greeters to tell patrons, “Everyone is using them. Why not you?” Thus, the shopping cart was born, facilitating much higher sales.

1952: The Barcode

Barcode technology was patented by Drexel Institute’s Joseph Woodland as he pondered ways to speed up checkout queues and product stocking.

1960s: The Rewards Program

Supermarkets and other businesses once handed out S&H Green Stamps in proportion to what a shopper spent. Shoppers could use their stamp-filled booklets for discounted purchases later. Introduced in 1896 in other retail segments, Green Stamps took off in supermarkets around World War II, and their heyday was the ’60s. What is believed to be the last grocer to offer Green Stamps, a Piggle Wiggly in Columbia, Tennessee, stopped handing them out in 2011. The S&H Green Stamps pictured below are sourced from Cayobo under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

1962: The Supercenter

Grocer Meijer devised the first multidepartment “supercenter” in 1962, when it added 80,000 square feet to a supermarket in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The building was demolished in 2010 to make way for a modern Meijer store, though the company kept a ceiling beam, pictured below from Rossograph under the Creative Commons AttributionSharealike 4.0 International License. Called Thrifty Acres, the concept combined discount department stores and supermarkets. Among its 25 departments were separate men’s clothing, women’s clothing, children’s clothing, appliances, shoes and sporting goods. The first Walmart Supercenter concept opened in 1988, in Washington, Missouri.

1967: The Private Label

Convenience-store operator Joe Coulombe shifted gears to create a compact concept focusing on value and unique products, opening the first Trader Joe’s in Pasadena, California. That store still operates today, and the chain became known for an often-changing roster of quality private-label goods.

The operator masterfully circumvents what Choice Hacking calls the “choice overload effect,” the consumer tendency to be lured by just enough choice but overloaded by too much, said Choice Hacking founder Jen Clinehens. The idea is supported by Columbia University researchers, as well as psychologist Barry Schwartz’s book, Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less. “It’s obvious that fewer options can get people in stores, translating to more sales per square foot,” she said. Trader Joe’s has 4,000 SKUs compared to a full-line grocer’s 35,000-plus. “Their laser-like focus on those products creates a streamlined customer experience. Fewer products, no app, no coupons, no loyalty program, no self-checkout — it’s just a simplified, quality experience that’s fun. Shoppers see it as a little treat that’s affordable but feels more expensive.” The in-demand chain has 591 U.S. units and plans 24 new locations this year, eight of them in Southern California. To attract younger shoppers today, meanwhile, Walmart has launched its broadest own-label food line in two decades, Bettergoods. By this fall, the brand expects to offer 300 different products.

1974: The Price Scanner

The first product-identifying Uniform Product Code price scanner, made by Spectra Physics and NCR, was installed in a Marsh supermarket in Troy, Ohio. The first purchase was a pack of Wrigley’s gum.

1976: The Warehouse Club

Entrepreneur Sol Price introduced membership-based superstores to the grocery landscape in San Diego with Price Club, a brand now known as Costco. The location, pictured below, also is a Costco now, and the photo from RightCowLeftCoast is sourced under the Creative Commons AttributionSharealike 4.0 International License. Sam’s Club entered the category in 1983.

1980: The Health Food Focus

Paving the way for an explosion in organic and health food grocery concepts, John Mackey and Renee Lawson opened Whole Foods Market’s inaugural store in Austin, Texas. It was an offshoot of a store called SaferWay, a spoof of Safeway.

Whole Foods Market in Oakland, California

1986: Self-Checkout

Kroger rolled out automated checkout machines in Atlanta, and about two decades later, the tech took off. Another 20 years later, Walmart, Target, Dollar General and others are pulling back on self-checkout lanes.

1989: Online Shopping and Home Delivery

Brothers Thomas and Andrew Parkinson founded online grocery delivery service Peapod. Amazon Fresh grocery delivery service started in select cities in 2007.

1990s: Loyalty Updates and Locavores

Customer-loyalty cards with barcodes largely replaced the outmoded Green Stamps in the 1990s, though now, apps are replacing some loyalty cards. Increasing demand for locally sourced grocery items surged in the 1990s with a growing environmental awareness. The local-food market grew from $5 billion in 2004 to $12 billion in 2014, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and it continues to snowball.

2009: Focus on Price

Heightened competition between grocery chains, forced many grocers to adjust their business models to focus more on price and value. Inflation has thrust such concerns back into the spotlight now, though needed price cuts will arrive soon, experts agreed. Some are already here. Late this spring, Target said it would cut prices on 5,000 frequently shopped products. Aldi and other grocers announced cuts, too. Yet food inflation persists at the grocery industry’s prime competitor, restaurants. Just over 61% of U.S. restaurant operators said they’ll raise menu prices in 2024, according to restaurant manager software provider Restaurant365.

2020: Supply Chain

Widespread supply chain shock started to spell higher prices for supermarkets. In 2021, food-and-beverage revenue rose to more than 6% over total costs, according to the Federal Trade Commission. In 2022, Walmart saw an operating profit of $21 billion, Amazon saw a total operating income of $12 billion and Kroger reported an operating profit of more than $4 billion.

2022: M&A

In 2022, Kroger proposed an acquisition of Albertsons. The FTC filed suit to stop the purchase, and Kroger and Albertsons said they would spin off 579 stores and other assets to a wholesale company, C&S Wholesale Grocers, for $2.9 million. The still-in-the-works purchase faces other lawsuits. Large capital investments like loading areas for buy-online-pick-up-in-store, digital shelf labels, just-in-time inventory systems, streamlined logistics plans and artificial intelligence have crowded out most large independent operators, said Regan Amato, executive vice president and manager of JLL’s Arizona retail platform. “There are very few one-offs left these days.”

2024: Artificial Intelligence

AI promises big premiums for grocers: an estimated $113 billion in combined efficiencies and new revenue opportunities by 2025, according to a Grocery Doppio report. Called The Times They Are A-Changing: The Impact of AI in Grocery, it’s based on data from Incisiv and Wynshop. Of 152 grocery executives surveyed, 73% expect AI to embed in most or all of their software by 2025. Respondents expect AI to eliminate an estimated 18% of store associates and resolve an estimated 53% of shopper queries.

Senior communications director Aaron Ricadela wrote in an Oracle blog entry that AI will help grocers more efficiently spot demand signals, fulfill e-commerce orders by robot, reduce food waste, experiment with prices before broad product rollouts, personalize promotions and allocate inventory to avoid excesses and stockouts. AI vision applications already can reduce shrinkage by identifying shoppers who pocket items, cashiers who don’t scan all items and customers who purposely pass products over scanners without registering barcodes, he noted. According to the and survey, consumers expect AI to play enhanced roles in product search, checkout and online ordering.

By Steve McLinden

Contributor, Commerce + Communities Today